Consider the Lilypads

Viewing artists as systems thinkers on the occasion of the inaugural Nxt Museum Realtime exhibition, 'Lilypads: Mediating Exponential Systems'

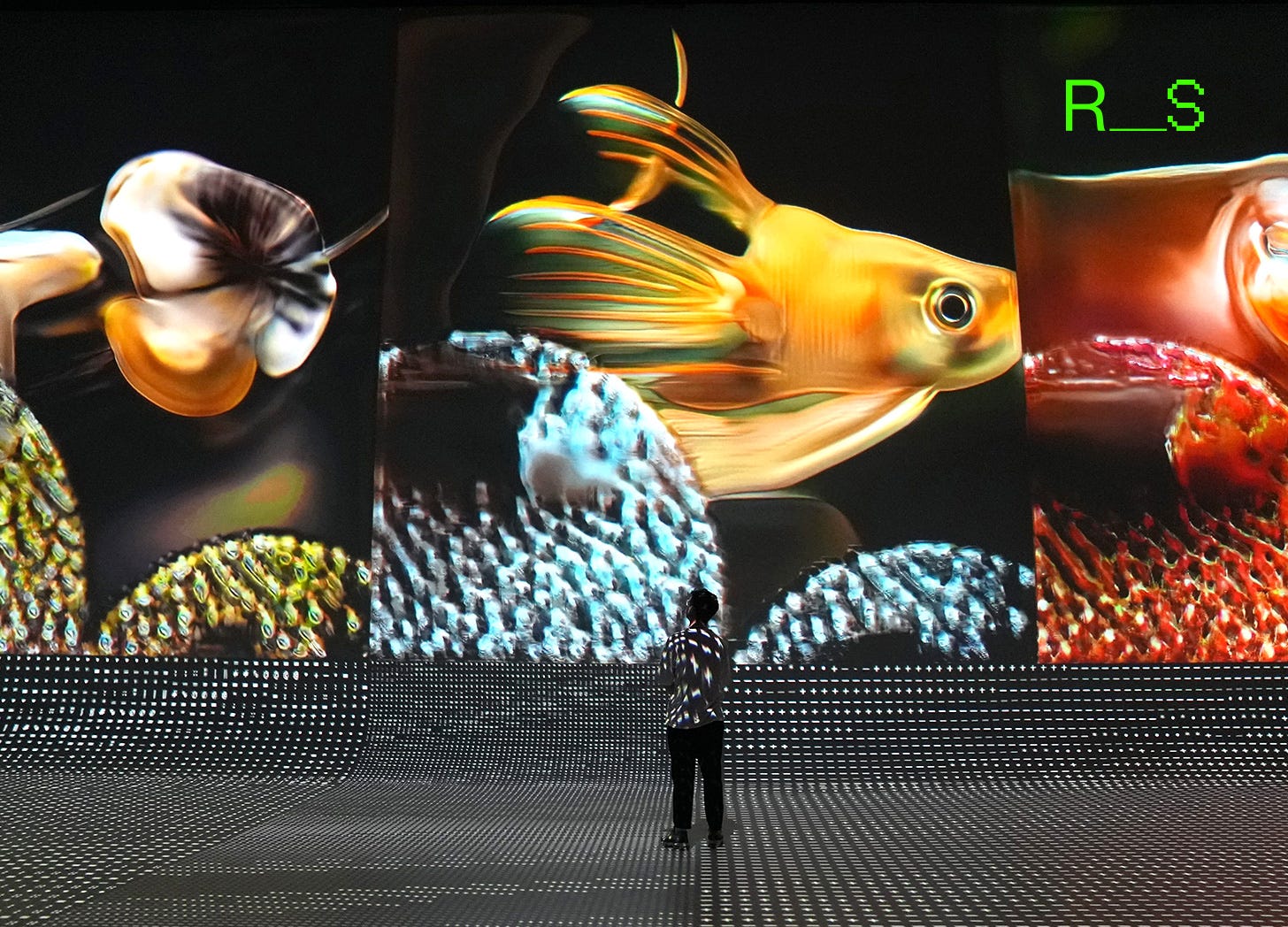

Earlier this month we launched Lilypads: Mediating Exponential Systems at Nxt Museum. It’s the inaugural show for Nxt Realtime, the museum’s new rotating exhibition structure, which seeks to tackle big, thorny questions that lack easy answers. (On-view in Amsterdam through the end of September—don’t miss it!)

Lilypads emerged from a series of exploratory conversations that Nxt’s first-ever Scholar-in-Residence and writer par excellence Charlotte Kent and I had, and were further refined through a couple public Twitter Spaces: Technology as Ecology (ft. Nancy Baker Cahill, Mark Dorf, Wendy W. Fok, Pinar Yoldas) and Artists Misusing Technology (ft. Minne Atairu, Michael Garfield, Parag K. Mital, and Caroline Sinders).

We were lucky to work with artists Amelia Winger-Bearskin, Entangled Others Studio with Robert M. Thomas, and Libby Heaney, who met our provocation with a ridiculous degree of rigor, artistry, and professionalism.

These ideas continue to echo in my thinking as I navigate the ongoing weirdness of art and technology. Below I’ve shared my curatorial note to introduce the show.

In popular imagination, lily pads often evoke ideas of safety and mobility, places frogs jump to evade a predator. This may be the short-term reality for a frog, but if the growth of lily pads—along with other species of lilies or pondweeds—is not held in balance with the rest of the ecosystem, it can choke the flow of resources that sustain other pond-dwellers. The pond, much like our planet, is a finite environment, not an exponential one.

In his 2002 book Seeing the Forest for the Trees, Dennis Sherwood outlines the following scenario: “A colony of frogs is living happily on one side of a large pond. At the other side of the pond is a lily pad. One day, a chemical pollutant flows into the pond, which has the effect of stimulating the growth of the lily pad so that it doubles every 24 hours. This is a problem for the frogs, for if the lily pad were to cover the pond entirely, the frog colony would be wiped out.” He then asks: “If the lily pad can cover the entire pond in 50 days, on what day is the pond half covered?”

Those familiar with exponential growth will recognize that the answer to this question is day 49. This is the power of anything that grows based on multiplication rather than addition—depending on your perspective, it might initially seem harmless, but by the time it’s visible (day 49 for the frogs) it’s already too late. The scenario, based on a French riddle, is also referenced in the 1972 report Limits to Growth, a landmark document that argued the then-current pace of human progress was unsustainable given the planet’s finite resources. Exponential growth patterns are one of several ways that species can impact one another. Observations around complex and interdependent relationships, rather than simply looking at constituent parts in isolation, has been the profound offering of the field of study known as systems thinking. The impacts of exponential growth are understandably significant in making sense of how a given system might achieve balance—and the ways in which it might fall out of alignment.

In the last decade, “exponential technology” became a go-to phrase for describing the pace of growth in the tech and innovation sectors. As computers and self-learning systems improved, through technologies like machine learning, they not only got better, they got better faster. Like the exponential growth of the lily pads, the new capabilities these technologies have brought, once only imaginary, are exploding into view. The frenzied pace of change is represented in the hype cycles around buzzwords: NFTs, Web3, Metaverse, Generative AI. This notion of “going exponential” aligns with economic incentive structures that demand this type of growth at all costs; under the current market conditions, a company is only regarded as successful if it can achieve this explosive, runaway acceleration.

Much as we like to imagine our species as unique, human beings are not separate from the rest of the world. We are part of global and local ecologies, and our current habits are pushing many systems past the point of repair or regeneration. We see evidence in the natural world (extinctions, melting ice caps, erratic weather events) as well in social contexts (wealth accumulation among the top 1%, the erosion of the middle class, the rise of authoritarianism in nations across the globe). For the average individual, the pervasive feelings of loss and chaos can be overwhelming to navigate. What can any one person do to create the type of mass-scale systems change that will be needed to reverse course? Further, we feel pressed to create such impact rapidly, to attempt to keep pace with the systems bringing about destruction.

Therein lies the tension of the contemporary condition: exponentiality is simultaneously our undoing and perhaps our only saving grace. Our lily pads.

Marshall McLuhan famously described artists as a “distant early warning system,” the ones most able to pick up on currents that weren’t visible or legible to others. As we enter the next quarter of the 21st century, it’s also crucial to recognize the artists who operate as systems thinkers, who apply their creative talents not only for the production of resonant sensory objects but toward unconventional uses of emerging technologies and practices. By subverting expectations and reimagining inherited rules, the artists in Lilypads: Mediating Exponential Systems reveal and communicate truths about broader systems that hold the potential to provoke new approaches to the multifaceted obstacles we face.

For more information on Lilypads and Realtime, visit the official Nxt Museum website.