What is Accelerationism? A Primer on the Defining Philosophy of Our Time, Including Effective Accelerationism (e/acc), the Dark Enlightenment, & More

A beginner’s deep dive into the theory, history, key thinkers, subfields, critiques, and implications of accelerationism.

You may have seen accelerationism coming up more in the news. Or, if you’ve followed Reality Studies and/or Urgent Futures for a while, you’ve perhaps encountered it here. But I realized I’d never done a proper explainer on what accelerationism is, so, following in the vein of my degrowth and post-growth primers, below you’ll find the official Reality Studies accelerationism primer.

I’ve come to believe that accelerationism is the defining philosophy of our times. It’s a term that emerges from a complex history, which has produced a wide range of meanings (many of which are contradictory or at least opposed). As with so many buzzwords, it is exactly this ambiguity that lends it staying power; debate = continual propagation.

What is Accelerationism?

At core, accelerationism is about the relationship of culture, capital, and technology to speed, change, and transformation. A simple definition of accelerationism:

Accelerationism is the idea that the best way to bring about radical change in society is to speed up the very processes that shape society—even if those processes are part of the problem.

Accelerationism holds that, rather than resisting capitalism or techno-industrial modernity, we should push them to—or beyond—their limits in order to destabilize the status quo and potentially generate something new (and theoretically better).

This philosophy has been called “political heresy” in its rejection of the impulse to use democratic processes to rein in capitalism’s excesses. Accelerationists instead propose ramping capitalism and technology into overdrive to trigger transformative change. If something is breaking or broken in modern society, some might argue that what’s needed is to adjust or reform it—slowing it down. The accelerationist looks at it and says: break it faster.

But this is where a consistent definition breaks down. Accelerationism isn’t a single, unified ideology but rather a spectrum of ideas. To start, it helps to understand the term through a broad binary (though as we’ll see it’s much more complex than this!):

Left-wing accelerationists (or “left-accelerationists”) hope that accelerating technological and economic growth can be steered toward progressive ends, like equality and emancipation (i.e., use the engine of technology to shorten the work‑week, democratize abundance, and reach post‑capitalism).

Right-wing accelerationists (or “right-accelerationists”) embrace rapid growth and chaos in a far more nihilistic or even reactionary way—some believing it will hasten a collapse that allows a new (often dystopian) order to emerge. The burgeoning effective accelerationist movement in Silicon Valley, which demands technological progress and “innovation” at all costs to solve humanity’s problems, falls under this umbrella.

If you’re new to all of this, these ideas might sound a bit abstract or extreme. But accelerationism has shifted from obscure academic theorizing to the epicenter of politics—manifest in the words and actions of Elon Musk and Vice President JD Vance (to pick only the most visible American examples).

The structure of this primer is as follows:

Origins: Accelerationism by Any Other Name

Key Thinkers & the Evolution of Accelerationism

Criticism & Counter-Theories

Modern Implications & Discussions

I’ve endeavored to explain these ideas in accessible terms. If you already have the hang of any of the above, feel free to jump to subsequent section(s). By the end, you’ll have grip on the basics (and then some) of accelerationism.

And hey, if you know somebody who would benefit from this, please send it to them or share it:

Origins: Accelerationism by Any Other Name

Accelerationism’s roots stretch back long before the term itself existed. The impulse to speed up social forces has appeared at various points in history. While today’s most visible manifestations of accelerationism are right-leaning, its origins actually begin as a leftist response to capitalism.

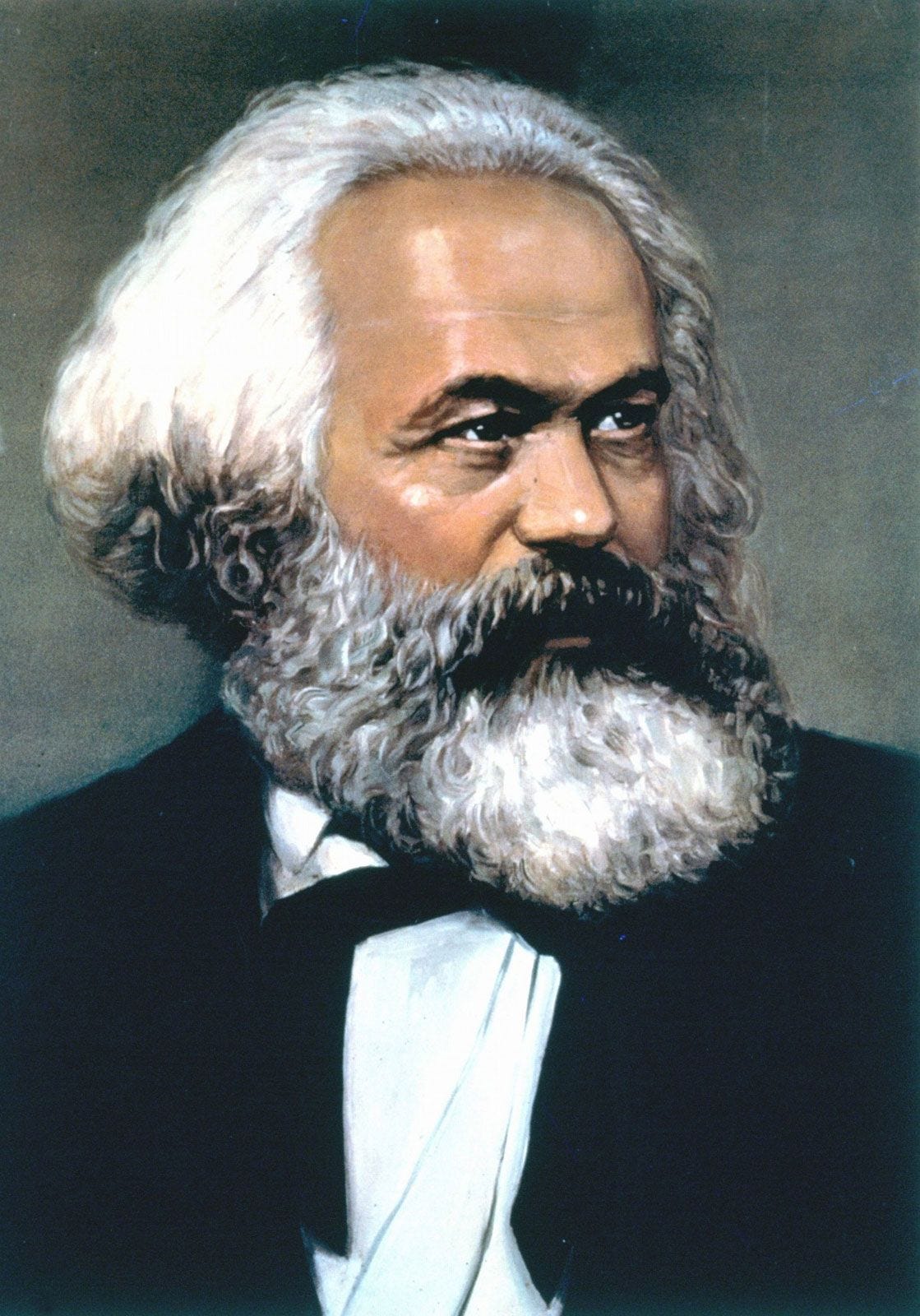

Karl Marx

Many scholars point to Karl Marx as an origin point. In the 19th century, Marx observed that capitalism, by its very nature, constantly revolutionizes the means of production and intensifies economic activity. He believed this intensification of capitalism would eventually undermine itself and prompt a revolutionary collapse.

In his 1848 speech, “On the Question of Free Trade,” Marx noted that free-market capitalism “breaks up old nationalities and pushes the antagonism of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie to the extreme point. In a word, the free trade system hastens the social revolution. It is in this revolutionary sense alone, gentlemen, that I vote in favor of free trade.”

In other words, Marx suggested that pushing the system to its limits could bring about its end—a core tenet of what we now call accelerationism. (Note: Marx was not advocating reckless chaos; he was analyzing how economic forces might dialectically lead to revolution. Still, subsequent thinkers have taken inspiration from this hurried demise theory of capitalism.)

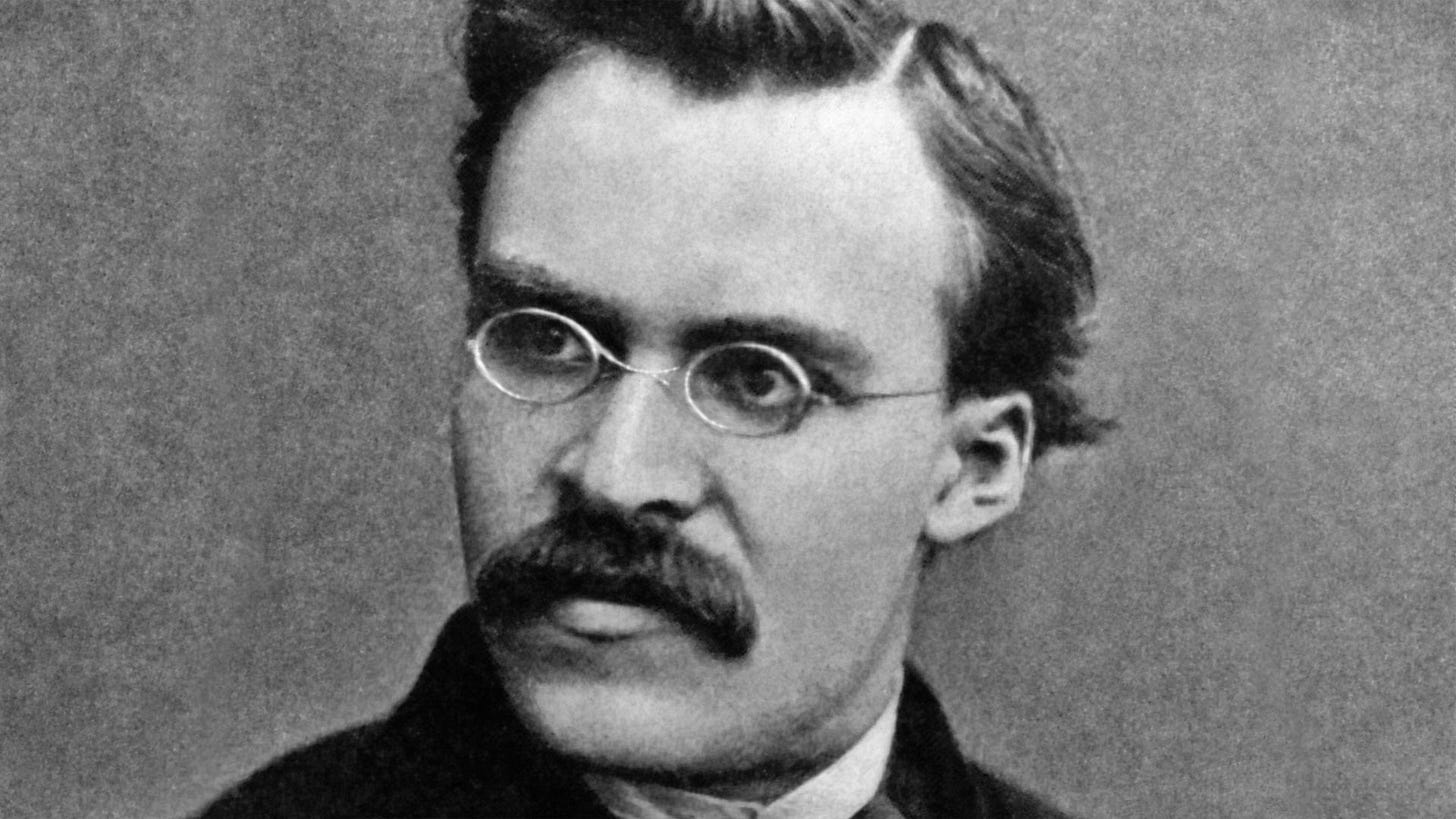

Friedrich Nietzsche

In the realm of philosophy, meanwhile, Friedrich Nietzsche offered an exhortation that accelerationists often cite as precursory. In a fragment published posthumously in The Will to Power, Nietzsche wrote that “the leveling process of European man is the great process which should not be checked: one should even accelerate it.”

This cryptic advice—to welcome the leveling, homogenizing forces in modern society and speed them along—can be read as an anticipation of the accelerationist stance, though Nietzsche’s context was quite different, addressing cultural stagnation in Europe. (What I hope is already emerging in this primer is that contemporary accelerationism is a composite of ideas pulled from different and oftentimes paradoxical sources—which in turn have been decontextualized, and that is certainly the case with Nietzsche’s ideas).

The Futurists

By the early 20th century, the ethos of acceleration, if not the term itself, surfaced in some artistic and political movements—notably among the Italian Futurists. In the Manifesto of Futurism, poet Filippo Marinetti writes:

Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggresive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

and

We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

This worship of speed and machinery embodies the accelerationist belief that rapid progress and technology are rejuvenators of society—and the danger and violence that come with them are necessary byproducts (also an implicit commitment of accelerationism).

With the Italian Futurists we also find powerful foreshadowing of the entanglement of accelerationism and nationalism that would crystallize in the 21st century; Futurism is understood to have influenced the development of fascism in Italy, and the second-wave futurist movement directly supported the Mussolini regime.

Pop Culture, Political Activism, & Postmodernism

The 1960s brought both pop culture and theoretical foreshadowing(s) of the accelerationism to come.

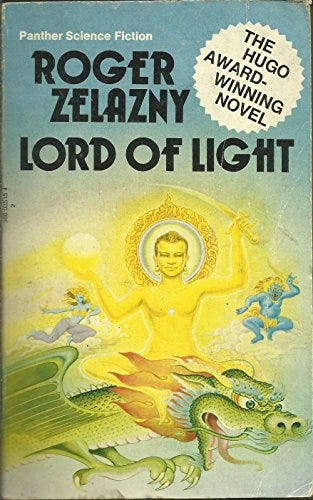

Notably, the word “accelerationism” itself made a debut in 1967…in a science fiction novel. Writer Roger Zelazny uses the term in his book Lord of Light to describe a faction that wants to hasten societal advancement.

Meanwhile, activists in the ‘60s often debated whether creating or enflaming crises could expedite revolution. Some currents of student and leftist movements flirted with the idea that heightening the contradictions of capitalism (i.e., encouraging its excesses or provoking state crackdowns) might quicken its downfall.

The first sustained philosophical development of accelerationist ideas came from the philosopher duo Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, who, in their landmark 1972 book Anti-Oedipus, posed a set of questions about what constitutes revolutionary activity:

“[W]hich is the revolutionary path? Is there one?—To withdraw from the world market…. Or might it be to go in the opposite direction? To go still further, that is, in the movement of the market, of decoding and deterritorialization? For perhaps the flows are not yet deterritorialized enough, not decoded enough, from the viewpoint of a theory and a practice of a highly schizophrenic character. Not to withdraw from the process, but to go further, to "accelerate the process," as Nietzsche put it: in this matter, the truth is that we haven't seen anything yet.”

Deleuze and Guattari appear to suggest that revolution won’t come by halting capitalism, but rather weaponizing its own processes against itself.

To clarify for those unfamiliar with this text: the authors refer to capitalism’s “schizophrenic flow” of desire and money, which serves to uproot and transform social relations (what they call “deterritorialization”). They argue that capitalism hasn’t yet done enough to achieve a real breaking point—and wonder if the truly revolutionary activity would be to move with and amplify these schizophrenic flows in order to ultimately break capitalism, rather than trying to oppose them. It’s easy to see why this “accelerate the process” passage is often cited as a theoretical birth of accelerationism as we understand it today.

Other French thinkers added to this proto-accelerationist thread. Jean-François Lyotard, in his 1974 book Libidinal Economy, abandoned orthodox Marxism, which asserts that communism will be an inevitable consequence of capitalism. Lyotard instead embraces the intense “libidinal” drives of capitalist society (money, desire, production), urging an immersion in its flows rather than a moralistic critique. Jean Baudrillard, in his 1976 book Symbolic Exchange and Death (and elsewhere), talks about pursuing “fatal strategies”—playing out the logic of the system to its extreme end so that it self-destructs or transforms (i.e., if the system feeds on information, one might try to hyper-saturate it with nonsense).

Both Lyotard and Baudrillard flirt with the notion that instead of opposing the system from without, one might ironically subvert it from within by exaggerating it. Again, these ideas weren’t called accelerationism yet, but have been retroactively recognized as such. Another French philosopher who contributed to the ultimate formation of accelerationist thought was Paul Virilio. In his book Speed and Politics (1977), he not only coined the term “dromology” (the study of speed and its impact on society), he argues that speed―not class or wealth―is the primary force shaping civilization (and an “engine of destruction” at that).

By the end of the 1970s, all the ingredients of accelerationism were in place: Marx’s insight about capitalism’s self-undermining speed, Nietzsche’s injunction to push forward, the Futurists’ love of speed, and the French theorists’ notion of riding capitalism’s wave. But they hadn’t yet been united into a guiding philosophy.

Key Thinkers & the Evolution of Accelerationism

Nick Land and CCRU

Accelerationism as an identifiable intellectual movement truly took shape in the 1990s, in an unlikely incubator: the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (CCRU) at the University of Warwick in England. The CCRU was a rogue research collective of young philosophers and writers fascinated by cyberpunk science fiction, rave subculture, continental philosophy, and the possibilities of emerging technology.

Two notable members were Nick Land and Sadie Plant, often credited with founding the CCRU. If accelerationism has a “mad scientist” figure, it would be Nick Land.

In the mid-90s, Land wrote a series of wild, visionary texts that read like theory infused with sci-fi horror—describing capitalism as an intelligent alien force or an uncontrollable techno-system that is escaping human control. Land’s writings (later collected in Fanged Noumena) laid the groundwork for what we now call right-wing accelerationism (or sometimes “cyberpunk accelerationism”).

Land drew on the earlier French ideas and pushed them further. He viewed capitalism itself as a self-propelling techno-cultural evolution, a positive feedback loop where technology and markets feed each other in exponential growth. In Land’s eyes, capitalism was not just an economic system, but a runaway process—“a self-escalating techno-commercial complex,” as he later put it. The CCRU under Land’s influence became known for a kind of ecstatic nihilism: they celebrated the idea that human agency was becoming irrelevant, overtaken by the accelerating “machinic” processes of capital and tech.

Land’s essays were known for their raw, hallucinatory, almost cyber‑gothic prose. “Meltdown,” for example, describes a scenario of an Earth transformed into a “techno-slime” by self-replicating machines. A key concept he introduces is “teleoplexy,” in an essay of the same name, which refers to the the compounding intelligence of capital as it evolves—essentially dismissing the prospect of capitalism’s self-destruction imagined by left-accelerationists.

Mark Fisher, who was a CCRU member (before charting his own course), described their stance as an “exuberant anti-politics, a ‘techno-nihilism’ celebrating the irrelevance of human agency.”

“Capital revolutionizes itself more thoroughly than any extrinsic ‘revolution’ possibly could,” Land wrote later, arguing that trying to oppose or regulate capitalism was futile—the real revolution is capitalism’s own forward eruption. The conclusion for Land was: don’t resist—ride the tiger. This is accelerationism in the raw: surrendering to the runaway tech train in hopes it leads somewhere new, even if that “somewhere” might be the extinction of humanity. In the aforementioned “Meltdown,” for example, Land remarks that “nothing human makes it out of the near-future.”

It’s important to note that Land’s accelerationism was theoretical—he wasn’t advocating terrorism or immediate chaos; he was sketching a philosophy of history where technology and capital merge and spiral beyond control, potentially to a point called the Singularity (a hypothetical moment in which AI and tech growth become irreversible and self-sustaining, and displace humanity’s dominance on Earth).

Land foresaw this happening first in East Asia: in “Meltdown” he envisions China as the site of a coming techno-capitalist singularity that Western nations would struggle to contain. Notably, Land later moved to Shanghai and praised China’s rapid development as exemplifying accelerationism in action. By the end of the 1990s, Land had effectively sketched out the accelerationist worldview on the right: radical embrace of free-market forces, technology, and the breakdown of traditional structures—even democracy and morality—in pursuit of an unprecedented future.

This would eventually lead Land towards the fringe neoreactionary movement (NRx) in the 2010s, where he advocated autocratic techno-elitism (his infamous essay “The Dark Enlightenment,” argues democracy is a brake on acceleration and suggests CEOs-as-monarchs instead. This was later elaborated in his book of the same name. (I’ll be covering this in greater depth in a separate piece on how it has evolved through and because of the MAGA movement). That shift also tinged his ideas with racist overtones that caused many to distance themselves from him. Nonetheless, Land’s ‘90s writings remain foundational in accelerationist thought; he has been dubbed the “godfather of accelerationism.”

Mark Fisher, Nick Srnicek, and Alex Williams

While Land was pushing a delirious pro-capital accelerationism, others began to return to the idea’s origins: Could these ideas be actioned toward leftist goals? Fisher, along with younger thinkers like Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams, took inspiration from Land’s diagnosis but not his prescription. They observed, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, that traditional left politics seemed stuck and ineffective, almost resigned to managing decline.

In his landmark Capitalist Realism (2009), Fisher cites both Frederic Jameson and Slavoj Žižek writing, “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” a quote that’s become famous for capturing this sense of paralysis.

Instead of rejecting acceleration outright, however, Fisher suggested that “Marxism is nothing if it is not accelerationist.” He meant that Marx himself admired capitalism’s revolutionary thrust (as I outlined above), and that the left should reclaim that thrust of modernity rather than clinging to nostalgia.

Writing under his blog k-punk, Fisher wrestled with how to reconcile the CCRU’s dark visions with a humane left project. In “Terminator vs. Avatar” (2012), he critiques Land (the “Terminator” side) as having brilliant analysis but a “fatal” flaw in abandoning the human side. Fisher also coined the phrase “the slow cancellation of the future” to describe how our culture has lost the drive for progress (see: Ghosts Of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology, and Lost Futures). Capitalist Realism isn’t about accelerationism per se, but its conclusion calls for reclaiming a sense of possible future beyond capitalism—implicitly aligning with earlier left-wing accelerationist aims.

In 2013, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams published #Accelerate: Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics, a short manifesto that officially launched what came to be known as left-wing accelerationism (L/Acc). Their manifesto was a rallying cry for the left to stop playing small. They argued that neoliberal capitalism had stalled—it was no longer delivering broad improvements, only crises and inequalities. Meanwhile, the left had become oddly timid and localist, focused on protesting or escaping capitalism in micro-communities, rather than offering a grand vision for the future. Srnicek and Williams saw this as a dead end. In #Accelerate, they write:

“Accelerationists want to unleash latent productive forces. In this project, the material platform of neoliberalism does not need to be destroyed. It needs to be repurposed towards common ends. The existing infrastructure is not a capitalist stage to be smashed, but a springboard to launch towards post-capitalism.”

In other words, they advocated for taking the very infrastructure and innovations capitalism has created—big data, automation, global networks—and using them to build a new system beyond capitalism. They pointed to experiments like Project Cybersyn in Chile—an attempt in the early 1970s to cybernetically plan an economy—as a hint of how technology could enable democratic economic planning at scale. Why, they asked, should the left settle for hand-crafted local alternatives when it could leverage 21st-century science and engineering to radically transform society?

Building on the manifesto, Srnicek and Williams later wrote Inventing the Future (2015), where they dropped the term “accelerationism” (perhaps due to its growing controversial connotations) but continued the program of an ambitious, tech-savvy left agenda. They advocated for automation of labor, a Universal Basic Income, and the reduction of the work week—aiming for a “post-work” society where machines produce abundance and people are free from drudgery. This was essentially accelerationist thinking applied: accelerate automation to free humanity from toil, rather than fear it. Importantly, left accelerationists stress that this acceleration must be steered—they want more technological development, but under democratic control and directed toward egalitarian outcomes.

So by the mid-2010s, we see the formation of two major branches of accelerationism. To elaborate on the binary presented earlier in the essay:

Right-Accelerationism, exemplified by Nick Land, sees unfettered capitalist/technological acceleration as an end in itself (even if it’s inhuman or anti-democratic in result). R/Acc often dismisses attempts at social justice or regulation as “brakes” on the runaway train of progress.

Left-Accelerationism, via Fisher, Srnicek, Williams, and others, wants to hijack the controls and push toward post-capitalism, using the engine of progress for social good. As Srnicek & Williams put it, accelerationism for them means “[preserving] the gains of late capitalism while going further than its value system, governance structures, and mass pathologies will allow.”

The dialogue (and tension) between these two forms has been a defining feature of accelerationist discussion. The #Accelerate manifesto itself explicitly dissented with Land’s view, arguing that leaving acceleration to capital alone would lead to barbarism or apocalypse, whereas a guided acceleration could lead to new horizons of freedom.

Nick Land, unsurprisingly, scoffed at the left version. In an interview, he called the notion that technology can be separated from capitalism a “deep theoretical error.” He insisted that any attempt to plan or slow the spontaneous process (i.e., via egalitarian politics) is doomed, dubbing left-accelerationist ideas as basically a call to slow down, not truly accelerate.

Apart from these two main, opposed camps, other related offshoots emerged:

Techno-Optimism & Effective Accelerationism (e/acc): Futurists and Silicon Valley “visionaries” sometimes argue that accelerating innovation (AI, biotech, quantum computing, et al.) will solve problems like disease, climate change, even death. The “techno-optimist” stance is milder than full-on accelerationism, but in my experience it’s something of a gateway to right-accelerationism (especially since venture capitalist Marc Andreesen published his “Techno-Optimist Manifesto”). Starting with Silicon Valley Twitter circles in 2022, this more generalized techno-optimist stance has combined with the purported rationalism of the Effective Altruism movement to become “Effective Accelerationism” (e/acc). E/acc proponents claim that slowing down tech is a worse risk than pushing ahead; they genuinely fear stagnation. For example, they believe a super-intelligent AI, if achieved quickly, could devise solutions to poverty or climate change, and thus we should remove all obstacles to technological development. One such voice, philosopher James Brusseau, argues that any problems caused by AI should be answered with more AI innovation, not less. E/acc amounts to techno-utopian accelerationism: it trusts that speeding up progress will yield positive outcomes in time. (Critics retort that this view dangerously underestimates risks—more on that in a bit.)

Far-right adoption (late 2010s): Since the mid-2010s, some white supremacist and neo-Nazi groups started using “accelerationism” to mean deliberately hastening societal collapse through violence. They took the core idea (“speed up the breakdown of the current system”) and applied it to an ideology of hate: by committing terrorist acts or inflaming chaos, they hope to destabilize society and trigger a race war, after which they fantasize a white ethnostate will arise. Manifestos of several mass shooters (e.g., the 2019 Christchurch attacker) explicitly referenced acceleration, encouraging others to create the chaos that will burn down the current order. Online extremist forums talk about “acceleration” as a strategy—essentially, make things worse to achieve your revolutionary goal. It’s worth emphasizing that this violent extremist accelerationism is not what the original philosophers—even Nick Land—had in mind. It’s a rogue mutation of the idea, sharing only the name and the abstract tactic of “speeding up collapse.” Nonetheless, its emergence in headlines has given accelerationism a sinister reputation in recent years, prompting mainstream awareness and concern about the term (contributing even to the production of the piece you’re reading right now).

Accelerationism in art and culture on the left: A number of contemporary artists, writers, and theorists play with accelerationist themes. For instance, the collective Laboria Cuboniks published “Xenofeminism: A Politics for Alienation” (2015), which some describe as grounding left-accelerationist ideas in feminism. They advocate using technology to dismantle gender constraints (even speaking of “gender abolition” in an emancipatory sense)—a kind of cyborg feminism that clearly aligns with the idea of leveraging tech for liberation. Another example is Aria Dean’s concept of “Blacceleration,” merging black radical thought with accelerationism, arguing that the historical trauma of black experience under capitalism blurs the line between human and capital in a way that recontextualizes acceleration. These are niche, experimental ideas, but they show how accelerationism has permeated various intellectual subcultures (art, gender theory, race theory) as a tool for rethinking modernity.

Intellectual Debates: Within academia and philosophy, accelerationism continues to be debated and updated. Younger scholars on forums and blogs (like the subreddit r/CriticalTheory or blogs such as Xenogothic) hash out distinctions like Unconditional Accelerationism (U/Acc)—a more apolitical stance that says “just accelerate whatever, without a specific end in mind,” versus the conditional approaches of conventional left or right. There are also intersecting discussions in fields like Speculative Realism and Object-Oriented Ontology about nonhuman perspectives, which gels with accelerationism’s interest in in- and nonhuman systems.

Other Major Works

Here are a few other major works that have informed the development of accelerationist thought, and might be of interest to those wanting to go deeper:

Malign Velocities: Accelerationism & Capitalism (2014) by Benjamin Noys. This is a critical work against accelerationism. Noys—who actually coined the term “accelerationism” in its current usage in his 2010 The Persistence of the Negative—lays out a leftist warning that accelerationism is a dead end that risks either apologism for capitalism or outright disaster. He memorably labeled the CCRU/Land school as “Deleuzian Thatcherism,” implying they mixed radical theory (Deleuzian desire) with right-wing economics (Thatcher’s market worship). Noys’ perspective is important as a counterbalance: he sees accelerationism as offering “always promised and always just out of reach” solutions, a kind of mirage that ends up justifying the status quo by glorifying its momentum.

No Speed Limit: Three Essays on Accelerationism (2015) by Steven Shaviro. Shaviro is a cultural critic who wrote these essays to examine accelerationism in a nuanced way. He explores both the potentials and pitfalls, discussing figures like Land, Fisher, and even pop cultural artifacts that resonate with accelerationism. It’s meant to be accessible, a bridge between the high theory and everyday implications.

The Dark Enlightenment (2012–13) by Nick Land. A series of blog posts by Land that have since been compiled into a book. While the subject here is neoreactionary politics (arguing democracy should be replaced by more “efficient” authoritarian structures), it ties directly to Land’s accelerationism: he contends that democracy, egalitarianism, and other Enlightenment values are “decelerators,” slowing the inevitable techno-capital rush. The Dark Enlightenment is significant (and infamous) for linking accelerationist logic with far-right elitism, and this connection has fed into alt-right circles.

The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty (2016) by Benjamin Bratton. Bratton doesn’t call himself accelerationist, but his book about planetary-scale computing systems (“the Stack”) analyzing how technology is undermining nation-states, and proposing an open-ended design for the future, has been described as accelerationist in thrust. It’s a dense work in design theory and geopolitics that nonetheless feeds into the same discourse of how technology is reshaping sovereignty and what futures that portends.

The Question Concerning Technology in China (2017) by Yuk Hui. Yuk Hui provides a critique of accelerationism from a cultural perspective. He argues that accelerationism’s universal “speed up modernity” prescription may impose Western notions of progress on non-Western contexts, amounting to a subtle new form of colonialism. He points out that not all cultures have the same relationship to technology (citing different myths like Prometheus in the West), so a one-size-fits-all acceleration could steamroll diverse ways of being. Hui’s work is a reminder that accelerationism, born largely in Euro-American theory, might not translate neatly to every part of the world.

TLDR: the evolution of accelerationism spans from 19th-century economic theory, to avant-garde French philosophy, to ‘90s cyber-theory, to contemporary political manifestos, and into extremist propaganda. It’s a trajectory that went from academic obscurity to something The Guardian would call “the future we live in.”

Criticism & Counter-Theories

Given its penchant for shocking proposals, accelerationism has attracted significant criticism from various angles—moral, practical, and philosophical. Critics range from Marxist traditionalists to environmentalists to mainstream commentators, and everything in-between. Here are some prominent critiques and counter-arguments to various forms of accelerationism (which you’ll note run the gamut of political and ethical positions):

Deleuzian Thatcherism (Benjamin Noys): As mentioned, Noys was one of the first to call out accelerationism from a left perspective. He coined the phrase “Deleuzian Thatcherism” to accuse thinkers like Nick Land of essentially dressing up a Thatcher-era free-market zeal in radical theoretical language. Noys and others argue that accelerationism offers false solutions: it sounds revolutionary but in practice often just means letting capitalism run rampant and hoping for the best (which he argues is basically just neoliberalism). He points out the irony that accelerationists denounce the status quo yet embrace the very engine (capitalism) that produces that status quo. There’s a fear that accelerationism could slip into masochistic complicity (i.e., an “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” attitude). Noys also notes how accelerationist promises are perpetually deferred; there’s always the notion that the real transformation is around the corner, after we intensify things a bit more. This starts to sound like an excuse to avoid tangible political action now, essentially handing over agency to “the process” itself. In short, this critique warns that accelerationism might be an intellectual dead-end that capitulates to neoliberalism (in Land’s case) or to a naive techno-optimism (in some L/Acc cases) instead of doing the hard work of building a just society.

Capitalism’s Resilience (Franco “Bifo” Berardi): Italian theorist Franco Berardi, a veteran of 1970s radical movements, has been a vocal critic. He acknowledges that “acceleration is the essential feature of capitalist growth,” credits it with highlighting capitalism’s instability due to this speed, and argues that the core accelerationist hypothesis is flawed: it assumes that speeding up capitalism’s cycles will make it collapse, and that all its latent technological potentials will de facto blossom into a new system. Berardi argues that instead, capitalism is highly resilient precisely because it thrives on chaos and instability. It doesn’t need stable conditions or rational control to survive; it can adapt to crises (indeed, often profiting from them). So accelerating into a crash might just lead to a perpetual state of crisis rather than a clear breakthrough. He gives a blunt answer to whether acceleration will end capitalism: “quite simply: no.” Capital can absorb shocks endlessly, as long as no alternative is built. Berardi is also attuned to the human cost: acceleration (endless competition, information overload, precarious work) is causing widespread anxiety, exhaustion, and nihilism. Rather than doubling down on that, he suggests we need to reclaim time and slowness, a view aligned with movements like degrowth or the “slow” movement, which directly oppose the accelerationist ethos.

Degrowth and “Slow” Movements: Perhaps the antithesis of accelerationism is the degrowth movement (and related “slow” philosophies). Reminder to check out my degrowth primer and degrowth reading list! Degrowth advocates argue that endless economic growth and acceleration are leading to ecological collapse and social misery, and that we need to intentionally slow down production and consumption for a sustainable future. They promote localism, simplicity, and reduction of throughput—precisely what accelerationists deride as “folk politics” or romanticism. Proponents argue that accelerationism is a recipe for eco-disaster; we should instead be finding ways to downshift global capitalism to save the planet and improve well-being. There have been dialogues between the two; some have asked, could there be a hybrid “accel-decel” approach (accelerate clean technologies, decelerate destructive industries)? This is aligned with some so-called “post-growth” perspectives (I also wrote a post-growth primer and reading list). There are too many diverging ideas and sub-theories to account for them all here, but by and large, degrowth is a direct challenge to something like an acc/dec approach: it claims the cure for the ills of modernity is not more of the same at higher speed, but a conscious move to less and slower. A 2017 article on Uneven Earth explicitly contrasts accelerationism and degrowth, suggesting they’re almost opposite responses to the same crises.

Existential Risk, or “X-Risk” (Longtermists and others): From a more mainstream perspective, many worry that accelerating technology blindly is incredibly dangerous. In the AI research community and among “longtermist” thinkers (like those in Effective Altruism who focus on existential risks), the idea of not slowing AI development is frightening. They essentially argue the opposite of e/acc: that we must be extremely cautious and deliberate with powerful tech like AI to ensure safety and alignment with human values. The specter of an uncontrolled AI (the “grey goo” or Skynet scenario) is a direct counterpoint to e/acc. Even outside AI, technological-industrial acceleration has brought us to a climate crisis; many scientists say we need to decelerate emissions immediately, the opposite of an accelerationist approach to industry. So, from an environmental and existential standpoint, slamming the brakes seems wiser than hitting the gas. As one Sydney Morning Herald piece criticizing effective accelerationism puts it: opposing regulation and going full throttle on tech can be seen as recklessly dismissing the catastrophic risks.

Moral and Humanitarian Critique: Some critics emphasize the ethical problem of intentionally exacerbating suffering. Accelerationism, especially in its pure form, might entail accepting or even welcoming crises—economic crashes, social unrest, et al.—as the price for eventual change (“progress”). But what about the real people hurt in those crashes? This criticism asks: Do the ends justify the means? And what if the “ends” never arrive, as Noys argues, meaning people suffered for nothing but a failed theory? Left accelerationists try to distance themselves from this by saying they want to use progress, not cause pain. But right accelerationism is open to this moral objection. The specter of “worse is better,” the idea that making things worse for people now will magically produce a better tomorrow, is historically associated with disastrous strategies (and typically entail violence). Cultural critic Slavoj Žižek, who is actually sympathetic to bold radical strategies, has still said accelerationism is “far too optimistic” and deterministic, counting on one inevitable outcome of chaos (revolution or new order) while ignoring that chaos can also lead to fascism, barbarism, or endless decay. In an essay for Compact, Žižek analogized accelerationism to Freud’s death drive, a destructive drive with no guaranteed positive outcome.

“Imposing Western Models” Cultural Critique (Yuk Hui): As mentioned, Yuk Hui and others caution that accelerationism carries a whiff of Western-centric historical thinking. It assumes that all societies must go through the same fast-track modernity to reach some new stage. This is reminiscent of the 19th-century idea that “backward” nations must develop like Europe did—an idea often used to justify colonialism. Hui points out that non-Western cultures might have different conceptions of what a desirable future is, or how technology should relate to life. For example, a society with more communal values might not want an AI-driven, hyper-capitalist future, even if it’s “advanced.” Thus, trying to accelerate everyone along one path could erase cultural diversity and replicate imperialist attitudes. A counter-theory here is pluralism, the idea that we should let multiple modernities unfold at their own paces, possibly learning from indigenous or slower ways of life rather than subsuming them.

Psychological/Spiritual Critique: Some critics take a humanistic approach, asking: What does acceleration do to our minds and souls? They note rising rates of depression, anxiety, and a sense of meaninglessness in advanced capitalist societies—trends that thinkers like Hartmut Rosa (who writes about “social acceleration”) attribute to the high-speed, high-pressure nature of modern life. Constant change can be disorienting; humans need some stability and slowness for reflection, relationships, and happiness. From this angle, accelerationism could be seen as a nihilistic embrace of exactly what’s tormenting people. By taking a “pedal to the metal” approach, rather than trying to mitigate the pace of life (through, say, mindfulness, community building, or valuing time off), accelerationism sounds inhumane or at least tone-deaf to the very real burnout and alienation many feel. The counter-theory implied here is a kind of human-centered gradualism—the idea that progress should be calibrated to human needs based on evolutionary processes, not just abstract historical engines.

Political Feasibility: Practically, many ask: even if one agreed with accelerationism, how on earth would you implement it? For left-accelerationists, this means who is doing the steering? If the plan is to use the state or some new institution to drive technology in a socialist direction, how do we get from here to there? Skeptics point out the left doesn’t have power in much of the world right now, and saying “we’ll seize the means of acceleration” is something of a pipe dream. In the meantime, uncontrolled acceleration is benefiting big tech companies and oligarchs, not the common people. For right-accelerationists, the question is what stops things from just descending into chaos or corporate tyranny. If you remove all regulations, and democratic oversight, do you really get a cool singularity utopia, or just extreme inequality and instability? There’s a political critique that accelerationism lacks a clear path from theory to action—except in the horrifying case of extremists interpreting it as a call to violence, which is obviously not what the philosophers intended.

For their part, accelerationists have tried to answer some critiques. For example, L/Acc folks would argue they do care about suffering and want to accelerate responses to suffering (like automating dangerous jobs, or quickly transitioning to renewable energy to combat climate change). They argue that the status quo is what’s causing suffering and ecological harm, and only a drastic transformation will save us by jolting us out of the status quo—thus, acceleration is the best (if imperfect) way to get there. They often acknowledge risks, but believe the risk of doing nothing (or of slow reform) is greater. Right-accelerationists, on the other hand, often just double down on “no pain, no gain”; they view things like equality or stability as sentimental baggage (or lately as an existential threat).

Modern Implications & Discussions

Hopefully it’s clear by now that accelerationism is contentious, to put it mildly; proponents of different political persuasions might hold diametrically opposed views.

Despite this divergent history, the prevailing form of accelerationism is right-wing, having found its place in the Trump administration, marrying politics to the desires of free market capitalism and the tech industry. VentureBeat called the 2024 election outcome an “accelerationist victory,” forecasting looser export controls and sunset clauses on safety rules—and Washington’s new “e/acc caucus” is pushing a hands‑off stance on AI and biotech, arguing that any regulatory damper puts the U.S. behind China (a go-to boogeyman for tech CEOs). This was nowhere clearer than in JD Vance’s speech at the AI Action Summit in Paris:

Across the Atlantic the mood is the opposite (or has been so far), with the European Union developing and working to implement the Artificial Intelligence Act, despite heavy push‑back from Meta and Google . That said, there is evidence that U.S. accelerationist rhetoric is even having an impact there; EU commissioners now hint at softening rules to avoid a talent exodus.

Whether one finds all this inspiring or disturbing, accelerationism confronts us with hard questions: If not capitalism as we know it, then what? If not by gradual reform, then how does big change happen?

Perhaps the ultimate value of accelerationism as an idea—even (especially?) for those who reject its propositions—is that it forces us to confront the trajectory we are on. I can certainly attest to this in my own journey. It dramatizes the choice between hitting the gas or stomping on the brake, and with 2025 already off to a volatile start, this debate is only going to intensify. I suspect that for many of you, where you land in your own thinking won’t be a blanket statement; different categories will demand different answers—accelerate here, decelerate there.

Whether we wanted to be or not, we are all now participants in a global accelerationist experiment. Where does this leave us, and what should we do about it? To quote Nick Land, “What does the process want, and what resistances does it provoke?” I’m still wrestling with my own thoughts and responses, some of which have already begun to appear across Reality Studies and Urgent Futures. No matter what, the answers we collectively envision for this question will define life on Earth for decades to come.

Did you learn something from this piece? Share it with a friend—it’s free!

Looking for more? Check out this piece on polycrisis and metacrisis:

SUCH a good primer, Jesse, thank you so much!

When I first read about #Accelerate (the book), I was deeply skeptical (important note: I haven't read it, so I hold this opinion loosely). Just feels like 'left accelerationism' is totally contradictory somehow, and I found myself resonating with pretty much all of the opinions in the 'Criticism and Counter Theories' section.

It's a tricky one. One the one hand, I agree with Žiżek and probably even Srnicek and Williams in that I feel the left has been totally immobilised and I fear that dark forests, cosy communities, localism, etc. aren't effective enough responses/strategies. But employing accelerationism as a strategy for the left feels like playing into the hands of the enemy (the enemy being Capital) somehow? Where does that leave me lol

Excellent piece Jesse