With Urgent Futures and Reality Studies, a big focus of mine has been communicating the very real and imminent dangers of the polycrisis. And, as many of you know, I live in Los Angeles. So you can imagine I’ve been working through a lot with regard to the Los Angeles fires.

For those who prefer to read, the essay follows from here. Audio versions are here, Apple Podcasts, and Spotify. And if you prefer video, watch on YouTube:

Before I dive in, a quick thank you to the community over on Goodpods; Urgent Futures is now in the Top 50 overall in the Technology category, and up to #17 on the weekly chart. When you do a podcast like this it’s always a bit unclear who the audience for it will be, and it often feels like you’re screaming into the void. So seeing it find like minds on Goodpods is super encouraging, and I just wanted to thank the community for their support!

Trying to describe this to folks outside of Los Angeles is difficult, for myriad reasons. There have been fires in California before. The geography of Los Angeles is weird, even for locals. People have misconceptions about the composition of the city. The list goes on. Trying to compare catastrophes is perhaps the most “apples and oranges” exercise once could attempt, but just to capture the impact on the Los Angeles psyche, think of this as something on the order of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, Hurricane Helene in the southeast, or even 9/11 in New York.

These are the most destructive fires in California history. Current estimates of the economic losses are as much as $150B, scorching over 12,000 structures—and with the fires still raging, those figures are bound to increase in the days and weeks to come. The 16 dead and 16 missing may not compare to the death tolls of the aforementioned disasters, but that belies the vast scale of destruction. Whole neighborhoods—not just homes but businesses, schools, parks—obliterated. Many of these structures under- or uninsured. How long will it take to rebuild these structures? Is it even wise to build them in an area destined for more such fires? Even those who have the means to do so will face labor and materials shortages. What if it takes 3 years to rebuild? What will they do in the interim? Where do young people go to school? Will they relocate? How will city, county, and state seek to stimulate the economy, and who will they prioritize? We already know how unhelpful the executive branch is about to get when it comes to the state of California.

The rental market had already become brutal in Los Angeles, how robust will consumer protections be against price gouging as thousands flood the market?

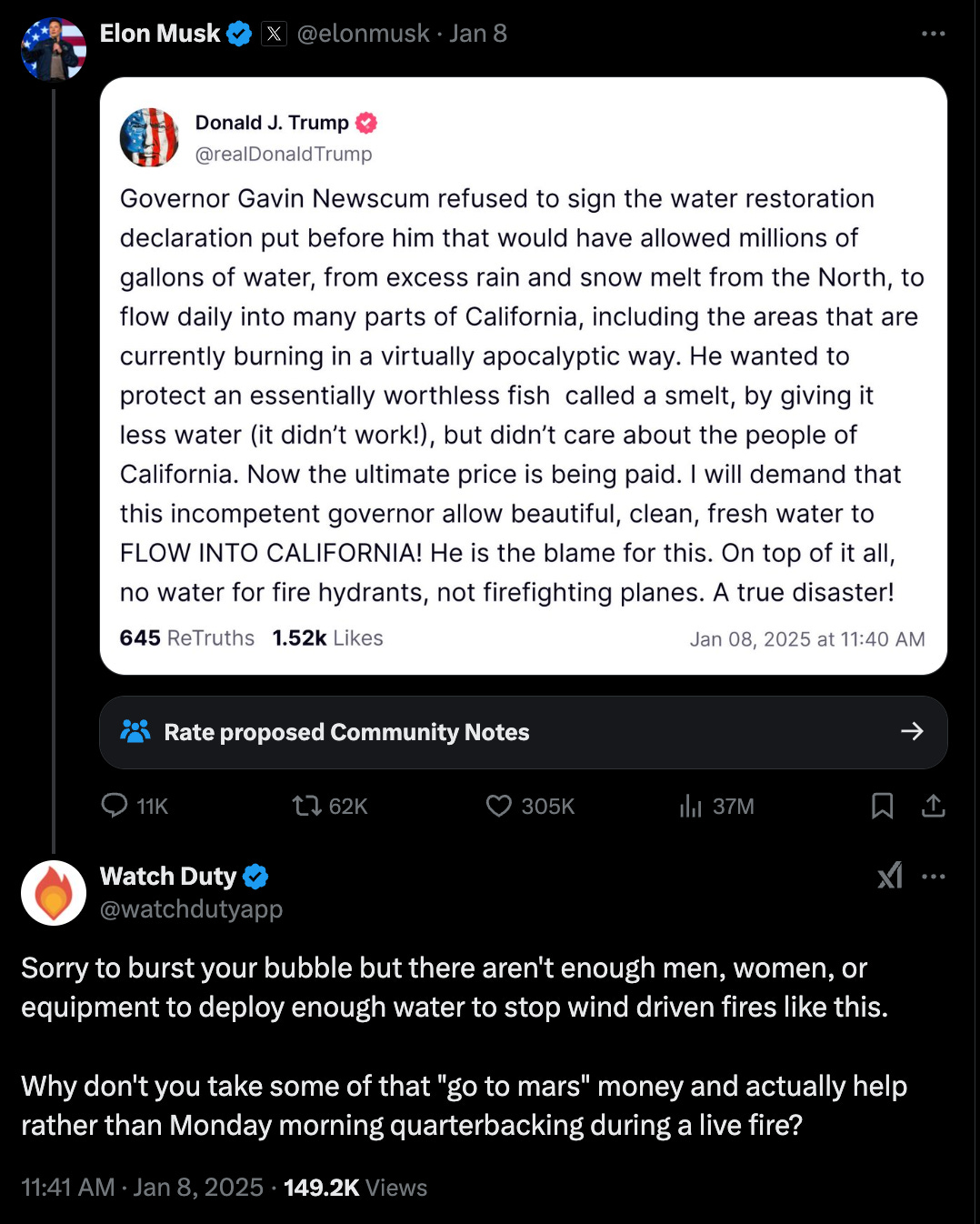

And we can’t underestimate the physical, psychological, and emotional toll. Few will soon forget the anxiety of obsessively refreshing the Watch Duty app, of going to bed wondering if it’s your neighborhood that gets the next evacuation order. Even by the most charitable read, state and local government failed to adequately prepare for this inevitability, and to communicate effectively during the critical first few days. And then there’s the disinformation, itself a wildfire of partisan jockeying and profiteering. Wildfire smoke carrying microparticles of lead, asbestos, formaldehyde, and other harmful chemicals have blanketed the air, breathed in by millions of humans and other animals. The downstream medical repercussions make me shudder. Many locals are wondering if it’s worth staying here.

Yes, I’m heartened by the outpouring of solidarity, mutual aid, donations, and support. Still, it must be said that however Los Angeles recovers, it will never be the same.

And if you’re paying attention, you recognize that all of this—the unprecedented “hurricanes” of fire, our inability to prepare for them, the systemic failures of our government, the exploitation for political disinformation—are symptoms of collapse in polycrisis. We’ve been seeing them more and more, all over the world. Remember last year’s floods in Brazil, Niger and Spain? Or Hurricanes Helene and Milton? Many call this our new normal, and that’s true in a general sense, but it belies the deeper truth. This is a cascade of new normals (plural); as the Earth heats, we will continue to witness events that dwarf prior ones in scale and impact. Somewhere, possibly even in Los Angeles again, we are going to see hurricanes of fire more violent than those burning right now. The “fire tornado,” for example, was only identified in 2003 and popularized during later California wildfires in 2018 and 2020. Now that almost seems quaint in comparison to the Los Angeles fires—and not because the fire tornado became any less scary as a concept.

For many of this channel’s audience, nothing I’ve just said will comes as a surprise. Earth is magical, but it is also fearsome. If you need a quick primer on the type of wreckage the Earth is capable of wreaking, I encourage you to listen to my conversation with Peter Brannen, author of The Ends of the World, on the previous five mass exctinctions:

Oil companies and the U.S. military, for their part, are already quite clear on this. Strategists at Shell produced a scenario planning report in 1989 that outlined the very aspects of climate volatility we’ve been experiencing this century:

Meanwhile, in the 1990s, the US Army War College described the emerging world order as “VUCA”—volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.

This VUCA context is a key pillar of the polycrisis, a term to describe the collective and interconnected nature of the many overlapping crises of the 21st century. If you want a deeper dive (but still pretty brief!), here’s my primer:

Explaining Polycrisis and Metacrisis

Last week, Leah Zaidi and I announced the “Plotting the Polycrisis” workshop for storytellers, which we developed for SXSW 2024. I received some questions about the term, and since it’s going to be a recurring theme on Reality Studies, I wanted to take a moment to explain it, as well as the related notion of the “metacrisis.”

Wealth will certainly play a role in where disaster strikes and how well people are able to respond to and recover from it. But, as my friend Michael Mezzatesta eloquently wrote: “in the world’s richest country, in one of the richest cities, in one of the richest neighborhoods, people’s homes are being annihilated by wildfires today. The truth is that no amount of wealth can protect us from climate disasters.”

Michael Mezzatesta: Why Isn't the Economy Working? An Economist's Case for Post-Growth | #23

Welcome to the Urgent Futures podcast, the show that finds signal in the noise. Each week, I sit down with leading thinkers whose research, concepts, and questions clarify the chaos, from culture to the cosmos.

Even for all that wealth, Los Angeles was woefully unprepared for this. North Carolina, for their part, had been positioned as a climate haven before Hurricane Helene ravaged it.

I pivoted my career to focus on Polycrisis and collapse exactly because all our science points toward one stark reality: we* are driving our planet toward uninhabitability. We know this, and yet we’re not making the appropriate changes quickly enough (if at all). Human civilization developed during a blissful period of stability after the last ice age 20,000 years ago. We have taken this stability for granted so thoroughly that we’re tearing it to shreds. What’s needed is dramatic change at the systems and individual levels.

Will the Los Angeles fires be the wake up call to make such change? Inertia is powerful, so I’m not optimistic, but for those who do want to treat it as such, I thought I’d take a moment to synthesize some of what I’ve learned through my Urgent Futures conversations to outline the root causes for the polycrisis and responses to consider.

*I’m sensitive to the problems associated with using “we” (i.e., “who exactly is ‘we’”?) Generally speaking those in the West, particularly Americans, are most to blame—using something like 20x more resources than their counterparts in the global majority—and therefore “owe” the most in cutting back, working to solve the problems, etc. This is to say nothing of the ultra-wealthy, whose rapacious energy appetites become so outsized I genuinely don’t know how they justify it to themselves (a recent Guardian report has shown that the world’s richest used up their 2025 carbon budget on January 10). That being said, because we are talking about global systems and events, there is a degree to which these issues really do touch all of us, and degree to which all of us will necessarily have to respond to them. I do not intend it in the convenient and totalizing way that reinscribes White hegemony.

The Fundamental Problem of Modernity

Polycrisis isn’t just about carbon emissions and volatile weather events; those are just the grabby, charismatic problems. The primary reason we have entered a state of collapse is because of something called “ecological overshoot.” Put simply: we use more than the planet can sustain, but all of our systems are predicated on pretending that is not the case so that we can stick to business-as-usual.

Neoliberal capitalism demands that the economy must keep growing. We have built an economy that doesn’t recognize other factors, such as human or ecological wellbeing, into its model of success. That growth mandate is the engine that drives all other human systems. But this is demonstrably not sustainable—”sustainable” here not used in the greenwashing sense, but in the literal sense; Earth does not have enough resources to sustain what we are currently using, and the global population continues to grow.

With population growth comes more demand for energy and resources which we do not have. And the “renewable” energy interventions we could be making are being stymied for the very simple reason that oil companies make more profit by continually selling oil and gas rather than the much more modest profit they would make implementing solar, wind, et al. Wim Carton and Andreas Malm outline this and much more in their excellent recent book, Overshoot, and I’ll be publishing my conversation with them within the next few weeks.

In typical ecosystems, negative feedbacks serve to constrain overpopulation of any particular species over time—whether through resource scarcity, disease, or otherwise. Because we are a clever species, we have devised ways to bypass the normal checks that would have constrained our numbers—primarily because we unlocked the magic energy of fossil fuels. But as these disasters reveal, there are consequences to carelessly using those energy sources. Climate change is one symptom among a host of others brought about by this approach to our lives on planet Earth. Even if we could solve the emissions problem tomorrow, we would still need to address overshoot—which is the underlying driver for biodiversity loss, soil depletion, microplastics, and so many other major modern crises.

The “Jackpot” View of Collapse

Hollywood has conditioned us to have the wrong impression of collapse. In movies and TV shows, collapse is a singular event. In reality, collapse is an ongoing degradation that we recover from less and less each time, until the structures of civilization cannot effectively operate anymore. We need a new narrative framework to understand it. It’s not the easy cataclysm of an asteroid strike or nuclear war. Our VUCA reality is and will continue to play out over decades.

Sci-fi author William Gibson has one such frame: the Jackpot.

In his 2014 book The Peripheral (which was adapted into a TV show in 2022), Gibson writes across two timelines, the early 2030s and the early 2100s. The world of the early 2100s is awash in cutting-edge tech: there are nanobots and flying cars and robots who people can inhabit as (physical) avatars. But there’s one detail that grates with this glinting chromepunk future: the population is a small fraction of what it is in the earlier timeline. Why?

In the world(s) of the story, between the two periods came an “androgenic, systemic, multiplex” cataclysm called the “Jackpot,” which wiped out most of the human population. So what exactly was this megacatastrophe? Protagonist Wilf Netherton describes the Jackpot as follows:

No comets crashing, nothing you could really call a nuclear war. Just everything else, tangled in the changing climate: droughts, water shortages, crop failures, honeybees gone like they almost were now, collapse of other keystone species, every last alpha predator gone, antibiotics doing even less than they already did, diseases that were never quite the one big pandemic but big enough to be historic events in themselves.

This framing of collapse has haunted me since I first read The Peripheral. And to hammer the point home, he later gave further context on his view of the Jackpot’s timeframe (incidentally, prompted by my pal Noah Nelson’s tweet at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in the West):

(Noah, by the way, runs an excellent publication + podcast called No Proscenium, which you should check out if you’re into immersive art, theatre, storytelling, et al.)

If you ask folks like ecologist and ecological economist William E. Rees, that start date 100 years ago might be a bit conservative. I’d bet he would say a Jackpot scenario began when the Industrial Revolution kicked into high gear in the early 1800s. You can get a crash course in his ideas—notably around ecological overshoot, why climate change is a symptom vs. a cause, and what we should collectively start doing about all of it—in my conversation with him. I can’t recommend him and his work enough:

Overshoot is and will continue to foster economic and political strife, things like resource shortages, inflationary shocks, wars, refugee crises, the rise of authoritarianism. Neoliberal economics makes certain people very wealthy and very powerful, and they will protect this power and wealth at the expense of the rest of us. Without intervention, this will accelerate collapse—all while the impacts of climate change (such as these fires) begin to hit us in earnest.

My mind also goes to a story I read last year. It documents the radical changes in climate that have taken place in the region historically known as Mesopotamia, particularly southern Iraq. The story highlights how, in a few short decades, a verdant city like Basra (once known as the “Venice of the East”) has become a desert. The opening paragraphs don’t mince words:

The word itself, Mesopotamia, means the land between rivers. It is where the wheel was invented, irrigation flourished and the earliest known system of writing emerged. The rivers here, some scholars say, fed the fabled Hanging Gardens of Babylon and converged at the place described in the Bible as the Garden of Eden.

Now, so little water remains in some villages near the Euphrates River that families are dismantling their homes, brick by brick, piling them into pickup trucks — window frames, doors and all — and driving away.

“You would not believe it if I say it now, but this was a watery place,” said Sheikh Adnan al Sahlani, a science teacher here in southern Iraq near Naseriyah, a few miles from the Old Testament city of Ur, which the Bible describes as the hometown of the Prophet Abraham.

These days, “nowhere has water,” he said. Everyone who is left is “suffering a slow death.”

Reading this, I couldn’t help but feel an uncomfortable echo of Los Angeles. An otherwise green region that is desertifying, especially after years of punishing drought. Of course, we need look no further than these fires to see how climate change accelerates collapse. And it’s not just the macro conditions of extraction and carbon emissions—Los Angeles has been built in a way that flouts Indigenous traditions which aligned with the realities of the land. Though human activity didn’t cause this fire (other than in the cases of arson), it created the conditions for catastrophe. The natural volatility of the Los Angeles river was tamed and paved over with concrete. Pavement—there and throughout the city—reduces the amount of water that soil can absorb. Non-native palms gobble water and create little shade, while invasive eucalyptus trees are far more flammable than native trees. Too little investment in forest and water management, too much in the police force. Controlled burns rejected by NIMBYism. I don’t mean to place blame at anyone’s feet; but we have collectively kicked the can on protecting ourselves from the very well understood threat of wildfires in this region. We still live in a time of relative abundance, so a place like Los Angeles will recover to some degree this time. But what about the next round of fires? And the one after that? Foolishness is a luxury we don’t have.

What can we do about it?

So, to recap so far: the underlying problem is overshoot, and we have bad mental models for the polycrisis, which will unfold erratically over decades rather than in a monolithic Hollywood catastrophe. No matter what we do, we will have to accept the reality of extreme climate events for the rest of our lives. We are not going back to an old normal.

But we can endeavor to preserve life—ours and all other Earthlings. It’s a cliche for a reason: every little bit helps. Just as all of the harms we’ve committed have multipliers on them, so too will our restorative and regenerative efforts. There is so much each of us can do. And in doing this we can live lives full of meaning away from hollow consumerism and flawed ideas of ‘progress.’

These can be distilled into three broad, related categories: adaptation, resilient innovation, and narrative shift.

Adaptation

On the morning of Tuesday, January 7, I had the privilege of interviewing Rupert Read for Urgent Futures—the episode will be out in a few weeks (Edit: it’s out now—I have included it below). It was kind of wild to be in dialogue with at the doorstep of these fires, to have his words in my mind as I witnessed rapidly unfolding destruction.

Rupert, among other things, is the co-author of Deep Adaptation, and now of Transformative Adaptation. These are two books I strongly encourage you to read in full.

The basic argument of Deep Adaptation is that we are already inexorably in a state of runaway collapse, having blown past too many of the planetary tipping points to have any hope of remedying them. The originator of the term, Jem Bendell, makes a persuasive (and depressing) case for this in original 2018 essay, which he updates for the 2021 book. As such, he argues that we must focus now on deep adaptation—finding what’s truly important and meaningful in life as society collapses. He proposes a “4R” method of inquiry for this task:

Resilience: what do we most value that we want to keep, and how?

Relinquishment: what do we need to let go of so as not to make matters worse?

Restoration: what could we bring back to help us with these difficult times?

Reconciliation: with what and whom shall we make peace as we awaken to our mutual mortality?

It’s certainly tough love, and some climate activists believe it overstates the reality, but I believe it’s still worth reading to face up to the bleakest prospect. The first stage of grief is denial. That’s where many of us currently are when it comes to the subject of collapse. Each of us individually is going to have to make our way through anger, bargaining, and depression to ultimately arrive at acceptance. For me, staring into that maw allowed me to release the idea that I’d have a future that resembled anything like what I’d hoped, which in turn allowed me to grieve for it, and for the suffering and instability that would color the lives of everyone I love.

Transformative Adaptation, coined by Read, takes a softer, though no less rigorous, approach. I’m just going to read a direct quote from the book here:

“[Transformative Adaptation] holds open the possibility that human-triggered climate change can – through societal transformation – be halted, and that it will not go ‘runaway’. TrAd holds open the possibility that ecological breakdown can – through societal transformation – be reversed; and that the complexities, wonders, and diversity of the natural world can be regenerated, restored. TrAd holds open the possibility that the extremes of economic inequality and injustice can – through societal transformation – be corrected. TrAd therefore holds open the possibility that societal collapse can – through societal transformation – be avoided, even yet, and that vibrant successor civilisations can emerge to replace today’s destructive and hegemonic model of Western civilisation.

These fires—especially when considered through the lens of mounting populist authoritarianism around the world—are asking us to face up to a future in which our material realities are going to be worse. We’ll spend more to get less, and new catastrophes will keep setting us back. Wars will exacerbate it, as will rising energy costs and other unfolding crises.

Under modernity, the Western world lost the plot. We’ve created societies where social alienation is rampant, where we are utterly disconnected from the Earth and from each other. Though there is no sugarcoating that our futures are going to get worse, there is simultaneously a way to recognize these futures as an invitation to rediscover forms of meaning that can’t be measured in dollars or followers—and new forms of innovation that put our skills to the test.

Resilient Innovation (RESIN)

When you think about the future, your mind probably goes to flashy wearables, holograms, AI, robots, flying cars, and other stuff like it from sci-fi movies. Technology has colonized the future. Under the economic growth narrative, technology is synonymous with “innovation,” and a primary vector for driving “progress.”

I’m not saying the above examples aren’t futuristic, I’m saying that our futures are more than just technology, and innovation does not have to mean repeating the same extractive, alienating processes that got us in this mess in the first place.

Looking at the challenges we face, genuine progress and innovation in the 21st century is not shiny new toys, it is rigorous evaluation of the processes of our living planet, and how we might better align ourselves with them—all without throwing away the best of what we’ve learned under Modernity. If we’re as clever as we think we are, we have to start applying our innovative faculties toward resilience. For simplicity’s sake—and because acronyms tend to communicate gravity—let’s call this ‘resilient innovation’ RESIN.

One example of RESIN I learned from Nate Hagens is the solar oven, which uses direct sunlight to cook food. He categorizes this as an example of a ‘goldilocks technology.’

Of course, some examples of RESIN will fit into current tech paradigms. Look no further than Watch Duty, a non-profit app that has done more to keep us up-to-date about the fires than any other tool, public or private.

Permaculture and agroecology are other examples of innovations that draw more from ancient wisdom than flashy new developments. One “technology” in this vein that I’m positively giddy about is mycoremediation, in which local fauna and fungi are used to heal toxic waste sites and reduce pollution. Check out my conversation with Danielle Stevenson, a true visionary in this field.

I was recently at a conference where I attended a session hosted by Indigenous Hawaiian folks, who referred to repackaging these forms of wisdom as “knew innovation,” poking fun at the Western impulse to brand everything as new in order to be exciting. I agree with both underlying ideas—it’s silly that we’re wired this way, and the phenomenon does actually works. I see no downside, for example, to spending our time supporting the development of ‘knew’ innovations vs. a new gig economy app that will atomize an existing industry. But this comes with caveats.

Narrative Shift

At the end of the day, systems change is about people. We all act in ways that subconsciously reflect our culture and place in time. Western culture has been globalized by U.S. hegemony, which means that most of us express the structures of Western modernity and neoliberal economics in how we think and make sense of the world.

This isn’t all bad, of course—but the ways that it is bad are quite bad. The so-called ‘human behavioral crisis,’ which I discussed with Phoebe Barnard on a recent episode, won’t be solved just by making political or economic interventions. What’s needed is a major shift in values, and the best way to achieve such a shift is through narrative.

Systems change takes time. We must, as Vanessa Andreotti reminds us, “hospice” modernity (full book here). This in part means that we will need to use the language of capital to prioritize and reward good ideas—all while we’re trying to simultaneously reign in and ultimately break the relentless growth narrative. I won’t claim to prescribe the particular tactics for this balancing act, except to say that it is critical that we all remain highly conscious and accountable to our ideals. Much of the ‘knew’ innovation we’ll need for the years to come will be thanks to Indigenous communities and leaders, and it will be imperative that Westerners do not co-opt this wisdom—intentionally or not—and that this labor is acknowledged and compensated.

Narrative can help foster a sense of shared purpose, as well as help people understand their place within this purpose—writing themselves into the story without becoming extractive actors. It takes no specialized knowledge to participate in the narrative and values shift. It’s something everyone can do.

Hellfire is maybe the most palpable image of apocalypse in the Western imagination—and living through the Los Angeles fires right now, I get why. It’s harrowing. The sights, sounds, and smells feel preternaturally wrong. Nothing I can say here will change the utter devastation of so many here in Los Angeles.

But if humans are anywhere as smart as we believe we are, we will treat this moment as a reckoning. In the original Greek, apokalypsis refers not to doomsday but to a revelation or unveiling. The present apocalypses keep revealing how fragile modernity is, how desperate the need for change is, and how overdue we are for transformative adaptation. So much has already been lost, but there’s also so much to save.

Tomorrow Urgent Futures is back on our weekly schedule, and we’re kicking off 2025 in a major way, with John Vervaeke, of Awakening from the Meaning Crisis fame. Be sure to subscribe on your favorite platforms so you don’t miss it.

Prefer an episode with a focus on the arts? Here’s a recent chat with world-renowned beatboxer and new media artist Harry Yeff (aka Reeps100):