Americans: You Need to Understand How Catastrophic an Invasion of Greenland Would Be—For YOU

What happens to Americans if the U.S. seizes Greenland? Let's get into it. (It's bad).

Right now, the most fervent political discourse in the United States centers around ICE, and for good reason. A paramilitary law enforcement arm that can act without transparency and accountability (embodied in Vice President JD Vance’s claim that ICE agents have “absolute immunity”) is not only a clear violation of the Constitution, it’s a moral stain, mirroring some of the worst authoritarian regimes in history.

And yet, as bad as ICE is, from a macro standpoint, the looming prospect of a U.S. invasion (or any other kind of “seizure”) of Greenland would be incalculably worse (and likely exacerbate the harms perpetrated by ICE). I get the sense that many Americans think such an invasion would be ambiently bad on moral grounds, but don’t seem to grasp that it would likely induce a catastrophe for them. For each of us, individually. Even the best-case scenario following such an action is nothing short of a wrecking ball to the baseline realities we’ve come to expect.

So I’m donning my polycritical foresight hat to help break it down. Make no mistake: we must do everything we possibly can to thwart this possibility.

Understanding the Bretton Woods System & NATO

To get the full picture, we need to do a quick historical survey.

One of the great misunderstandings about the post-WWII international order is that it made the world peaceful or just. You only have to refer to the 81 regime change interventions the US conducted between 1946-2000 to understand that this world order was neither peaceful nor just.

Indeed, the Cold War era was implicitly and explicitly violent, with no shortage of proxy wars and state-sponsored ‘regime changes’—American hypocrisy was baked in from the outset (in the messaging, the U.S. positioned itself as a champion of democracy and peacekeeping). But the system did do something that most of us alive today—most of all Americans—take for granted: in aggregate, it made the world less catastrophic.

Before 1945, great powers regularly fought wars that destroyed entire systems. Conquest and annexation abounded in international politics; borders were provisional and empires rose and fell through force. After 1945, that pattern stopped. While all manner of fuckery and violence persisted, the most lethal form of conflict in human history—total war between great powers—largely did. Regardless of how you feel about the American empire, that fact alone makes the postwar order one of the most consequential political developments in modern history (again, bearing in mind the utter hypocrisy involved in how America and its allies exerted military and economic might at the expense of other nations).

For the first time in living memory, power was expected to operate inside a web of rules (hence, the so-called ‘Rules-Based Order’). Institutions governing security, finance, and trade made predictability more valuable than coercion. States—especially the wealthy ones higher up in the global pecking order—still cheated, bent norms, and acted in bad faith, but broadly speaking, expectations changed. Borders were no longer treated as temporary frames until the next opportune moment for war and conquest. Smaller states gained a level of security that simply didn’t exist in earlier eras. Stability became the organizing logic of global politics.

The Bretton Woods system was the economic architecture that made this post-WWII security order viable. Designed in 1944 and implemented in the following years, it replaced the interwar chaos of currency wars, protectionism, and debt spirals with a system built on monetary stability, capital controls, reconstruction finance, and U.S. dollar supremacy. The dollar was pegged to gold (that is, until 1971, but that’s a story for another time); other currencies were pegged to the dollar; and institutions like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank were created to manage balance-of-payments crises and fund reconstruction rather than force austerity through collapse.

This mattered because economic breakdown had been a primary accelerant of fascism, imperial expansion, and world war. Bretton Woods reduced the likelihood that economic stress would boil over into great-power conflict. By privileging predictability over predation, it allowed global capitalism to expand without constant military seizure of territory. It was the economic “shock absorber” that made a world without routine great-power war imaginable.

And that stability made the money flow. By replacing zero-sum mercantilism with open trade, development finance, and relatively stable currencies, economies around the world became intertwined, middle classes expanded (we have to remember that the advent of the middle class was in itself a historical anomaly), and extreme poverty fell. Interdependence made war irrational for most states most of the time.

Democracy benefited in particular. Historically, democracies don’t survive constant external threat and economic chaos, and Bretton Woods reduced both. Security guarantees, reconstruction aid, and norms against territorial conquest created an environment in which democratic institutions could consolidate and persist in places like Western Europe and East Asia. This didn’t happen because humans magically became more ethical or just, it happened because the international environment became less volatile. To quote Berkshire Hathaway Vice Chairman Charlie Munger: “Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.”

The United States played a central role in making this work—not just by being powerful, but by binding itself and its currency to the very system it dominated. Alliances, institutions, arbitration, and rules constrained the types of historical aggression we would expect to see from an empire as powerful as the United States. That self-restraint reduced arms races around the world (even as, paradoxically, the Cold War was a highwire walk to avoid “mutually assured destruction”) and made U.S. leadership tolerable even when it was (often) resented—this is where the notion of the U.S. as the world’s “cop” emerges.

Formed in 1949 in the shadow of World War II’s devastation, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) was a catastrophic-risk mitigation device to reinforce the Bretton Woods system. Its core innovation was simple: an attack on one NATO member (of which there are now 32 across North American and Europe) would be treated as an attack on all. This mutual defense commitment decisively locked the United States into Europe’s security, ending centuries of great-power conflict. It’s worth noting that, again, this stability was fraught at best. Former Greek Minister of Finance Yanis Varoufakis (who more recently coined the notion of “technofeudalism”) famously equated NATO to the mafia.

But NATO further deterred the normalization of invasion and war in an era of nuclear weapons, froze borders that would otherwise have remained violently contested, and made escalation simply unprofitable in most cases.

Key to this was the United States’s restraint; it’s why the Iraq War was widely condemned two decades ago and why many condemn the Trump administration’s recent invasion of Venezuela. But, for as bad as those developments were and are, they pale in comparison to what an attack on a fellow NATO member would mean for the U.S. and for the world: jeopardizing whatever remains of the fragile stability that has held on for the past ~80 years.

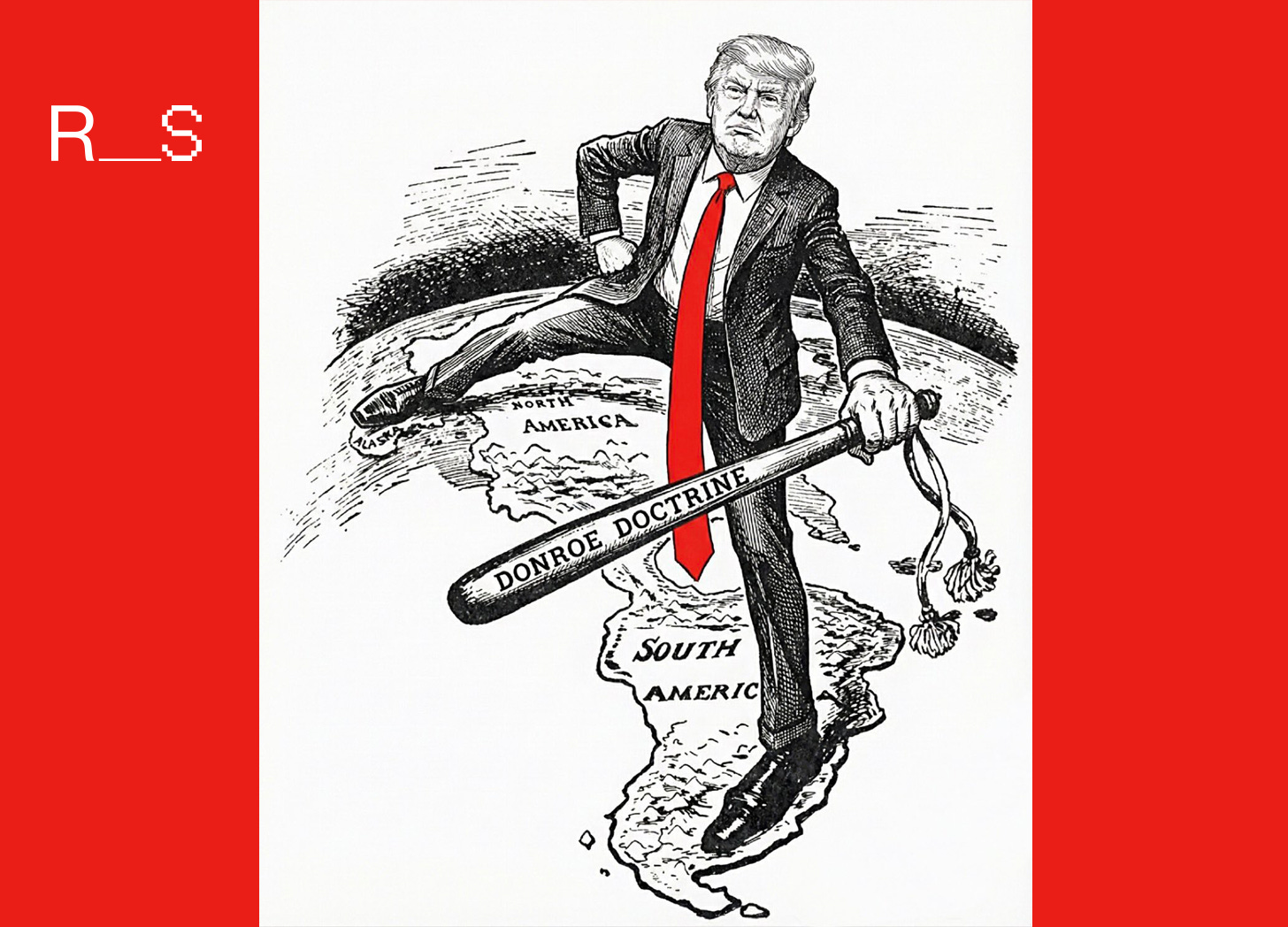

The Dangers of the Donroe Doctrine

This is where doctrines like the Monroe Doctrine—and its modern descendants, most recently Donald Trump’s ‘Donroe Doctrine’—become so dangerous.

When James Monroe established his eponymous doctrine in 1823, it was a defensive warning: Europe should stay out of the Western Hemisphere. At the time, it was less a legal rule than a geopolitical signal, initially enforced by British naval power and later by American strength. In a fragile post-colonial moment (we have to remember that the United States was barely even a minor power at this point), it aimed to prevent the return of European empires to the Americas.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—especially with Theodore Roosevelt’s corollary—it evolved into a sweeping claim of regional primacy. It became a justification for interventions, occupations, regime changes, and economic coercion across Latin America. What started as anti-imperialism morphed into a rationale for American imperialism.

That evolution exposes the core problem. The Monroe Doctrine rests on “sphere-of-influence” logic—the idea that great powers are entitled to privileged control over nearby regions (i.e., in their respective “spheres”). A rules-based international order rests on the exact opposite premise (however shoddily executed): sovereign equality, where states have the same legal rights regardless of size or proximity to power.

As opposed to post-1945 norms, the doctrine lacks reciprocity. It’s not a rule every state could adopt without contradiction. A system that tolerates carveouts can’t credibly oppose similar claims elsewhere. If the U.S. claims the Americas, there’s no justification for stopping from Russia from claiming Europe and China from claiming East Asia. In fact, this is precisely what the Donroe Doctrine argues should be the case. But once exceptionalism becomes acceptable in one context, it will spread to any others where deemed expedient and worth the effort. Apsirations to accumulate territory and power don’t naturally curb themselves (see: all of recorded history). Remember, we are at a moment in industrial history when the demand for energy sources, raw materials, arable land, and water sources is paramount. If this comes to pass, global cooperation goes out the window; everything is decided by the iron law of power.

Reviving nineteenth-century logic inside a twenty-first-century system—especially one whose successes were predicated on stability—is lunacy. That’s why the “Donroe Doctrine,” however it’s branded, is not just bad for U.S. credibility, it’s bad for the system that made the United States the richest nation in the history of the world. In other words: it’s a catastrophe for the everday realities of everyday Americans.

What Greenland Really Means

An American seizure or invasion of Greenland would be a hinge event, one that definitively shatters the postwar order and pushes the United States into a far more dangerous, unstable, and coercive world. And Americans would feel that shift almost immediately.

Greenland is an autonomous territory of Denmark, a full member of NATO. Any unilateral U.S. seizure—whether framed as a “purchase,” “protectorate,” “security necessity,” or whatever future term the Trump administration tries to use—would amount to an attack on a NATO ally. Not once since 1949 has something like this happened.

NATO’s credibility rests on the assumption that all members will recognize the sovereignty of all others. Once that assumption collapses, Article 5—which holds that an attack against one member will be considered an attack against all, necessitating each member to assist the attacked party—becomes meaningless. Allies would rightfully no longer trust U.S. security guarantees. European states would hedge, rearm independently (which they’re already doing!), and/or cut their own deals with rival powers. The alliance would go poof overnight, and the beginnings of a new world order would be upon us. Again, nobody has benefited more from this world order than Americans.

My colleague Leah Zaidi has produced a scenario that captures the likely emerging realities of a U.S. invasion of Greenland. Please read it in full below (here is a link to the full text if you’d prefer to read it that way):

As you can see, where Americans would feel the impacts of a U.S. attack on Greenland the most is economically. The dollar’s reserve status, low borrowing costs, stable trade flows, and global demand for U.S. assets all depend on one thing above all: trust that the United States is a stabilizing force, not a revisionist one. Once that trust is shattered, there is no reason for former allies not to use economic warfare as self-defense. They will rightly see themselves at war. Remember when the U.S. imposed sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine? Why would the U.S. be treated any differently? Because of the United States’s outsized role in the world order, that might look different in the particulars, but the broad strokes would be similar.

People seem to keep forgetting that Europe is America’s largest creditor. As umair wrote in HAVENS:

Who is the largest investor in America? This is what we call “Foreign Direct Investment” in macroeconomics, or FDI for short. Again, many people think it’s China or Japan, and they’re wrong. Badly wrong, in fact. China’s FDI in the US is just between 5-10%, given shadowy statistics. The EU’s FDI into America? It’s 45%.

So Europe is by far—by a tremendous, colossal margin—America’s largest investor. And that includes everything from stocks to bonds to property to companies and so forth. It represents nearly half of the world’s investment in America.

This is how important “the West” really is, and what it means. That the EU and America have these interlinkages which go so deep that they are genuinely foundational, in the truest sense of the word: Europe is the world’s biggest investor in America, by such a long way that it makes up half of the world’s total investment in America.

This is what is about to come undone.

The cascade will likely be swift and permanent, with long-tail impacts that stretch far, far into the future: higher interest rates, reduced dollar dominance, capital flight, sanctions on and rejections of American products, and long-term disintegration of U.S. economic privilege.

Americans—yes, you!—would feel this all throughout their economic lives: higher mortgage rates, more expensive credit, inflationary pressure, soaring costs, declining purchasing power, declining access to goods, and so much more that we can’t even currently predict. All this while having to spend billions or even trillions of dollars to maintain an active military presence in Greenland—especially if the U.S. wins, at which point the costs shift to sustaining occupation. For context, the Iraq War cost U.S. taxpayers roughly $2.4 trillion. Of course, with the U.S. now a rogue combatant, what’s to stop other nations from bringing the battle to American soil? And all of that doesn’t even include whatever the costs of the ongoing Venezuelan regime change will be, and assuming Trump doesn’t make good on invading the nine(!) other countries he’s threatened so far: Canada, Colombia, Cuba, Iran, Mexico, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Panama, and Syria.

Even absent such an attack, it’s reasonable to expect social and political turbulence on our home turf. Americans would live in a country permanently on edge: higher taxes for defense, fewer resources for social investment, more frequent international emergencies, and a political culture defined by fear and oppression rather than confidence and freedom. A U.S. seizure of Greenland would require the Trump administration to conduct sustained propaganda, emergency powers, and suppression of dissent to maintain the facade of legitimacy. You cannot normalize imperial behavior abroad without normalizing coercion at home (see: the Imperial Boomerang, which I wrote about here).

The same logic that justifies violating another democracy’s sovereignty will be turned inward against journalists, protestors, and political opponents. Here we come back to the awful question of ICE: if the public revolts against Trump’s invasion of Greenland, what do you think an insanely well-funded law enforcement arm that can act with impunity won’t do? History tells us that these are dark, dark places.

Listen, I know this is all super depressing, and I won’t pretend to have the answers on where we go from here. All I can say with unflinching certainty is that an invasion of Greenland would be a full-blown catastrophe for Americans—not just as a moral stain, but as an economic and political battering ram to the relative comfort we’ve experienced over the past few generations—and we should be doing whatever is within our power to shut down that possibility.

Stay safe out there.

Excellent enlightening article, thank you Jesse, it reads like an instuction manual for:

How to achieve WEF'S goals by 2030

You will own nothing and be happy

US will no longer be a super powwr

Great piece. Super inspiring for something I'm working on – will be quoting you. Thank you Jesse!